How Nestlé gets children hooked on sugar in lower-income countries

Nestlé’s leading baby-food brands, promoted in low- and middle-income countries as healthy and key to supporting young children’s development, contain high levels of added sugar. In Switzerland, where Nestlé is headquartered, such products are sold with no added sugar. These are the main findings of a new investigation by Public Eye and the International Baby Food Action Network (IBFAN), which shed light on Nestlé’s hypocrisy and the deceptive marketing strategies deployed by the Swiss food giant.

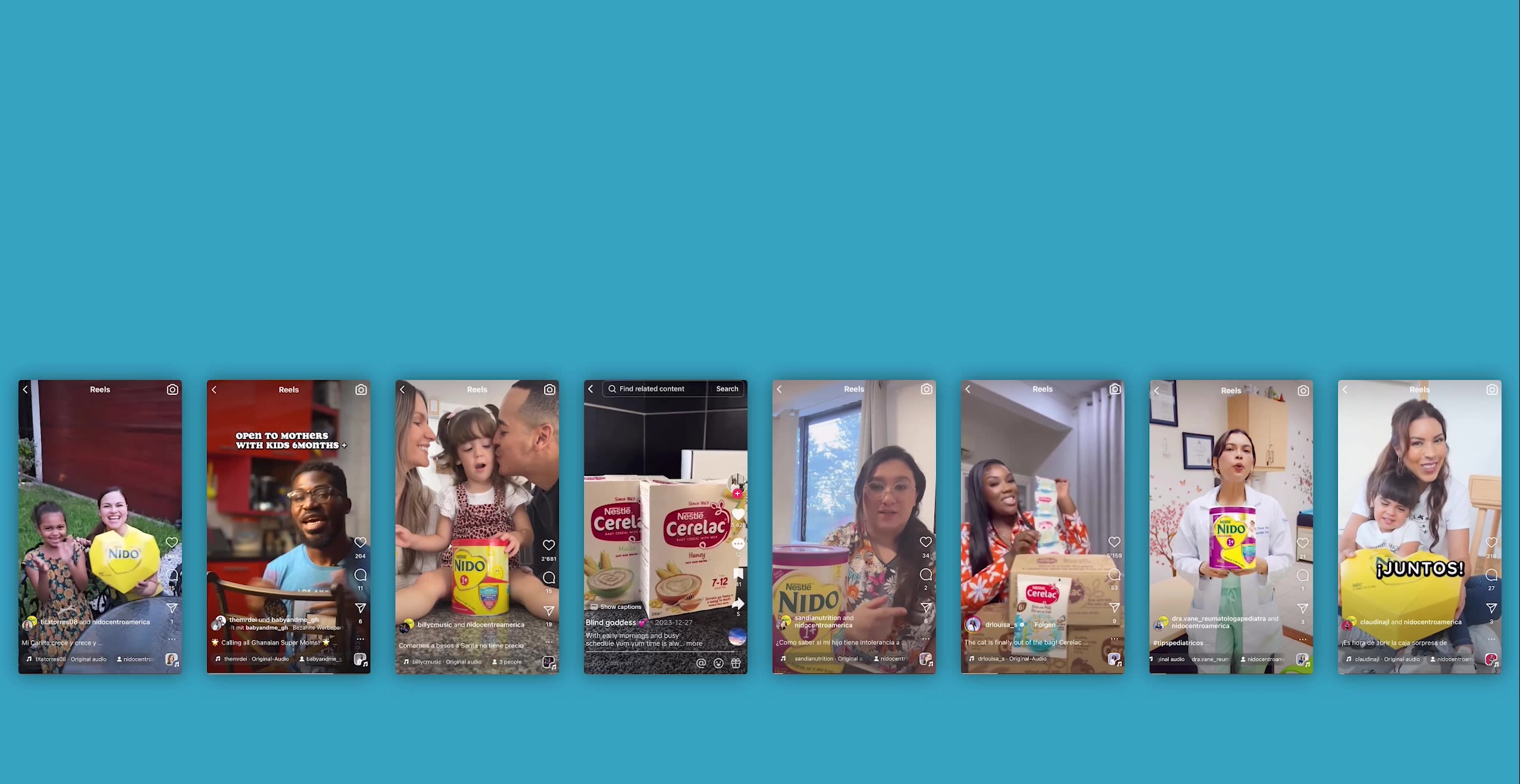

Meagan Adonis was 23 when she became blind as a result of a serious health condition. That same year she found out that she was pregnant, and was worried about the challenges of being a blind mum. She has now found her motherhood feet, and recently gave birth to a second child. Based in Johannesburg, South Africa, the “blind goddess” – as she calls herself – now documents her life for more than 125,000 followers on social media and chronicles her daily routine with her new baby.

Last year, Meagan posted several videos on TikTok promoting Cerelac infant cereals for babies from six months of age. “As you can see, I have a very active baby”, she explains in a video in December. “As a blind mum, feeding time is always an adventure! […] Now let’s go and prepare his favourite meal of the day. Little bodies need big support with Nestlé Cerelac being the perfect addition to our mealtime,” she assures her audience in a cheerful tone – while omitting to mention that this maternal counsel comes as part of a paid partnership with Nestlé.

Thousands of kilometres away, in Guatemala, a father films his energetic little daughter. “There’s no greater satisfaction than seeing a strong, healthy child”, says Billy Saavedra, a reggaeton artist better known as Billy the Diamond. “That’s why we prefer Nido 1+, which supports the development of her bones and muscles, as well as her immune system”, he adds in a video promoting the brand’s formulas for young children in March on his Instagram account, which has more than 550,000 followers.

The use of influencers, such as Meagan or Billy (and their children), is at the core of Nestlé’s marketing strategy to boost sales of its baby foods. This approach, which has become increasingly important in many sectors, allows companies to reach a broad audience, building on a sense of identification and relatability. Coming from parents with similar experiences, advertising messages are regarded as benevolent advice that can be trusted.

A growing market

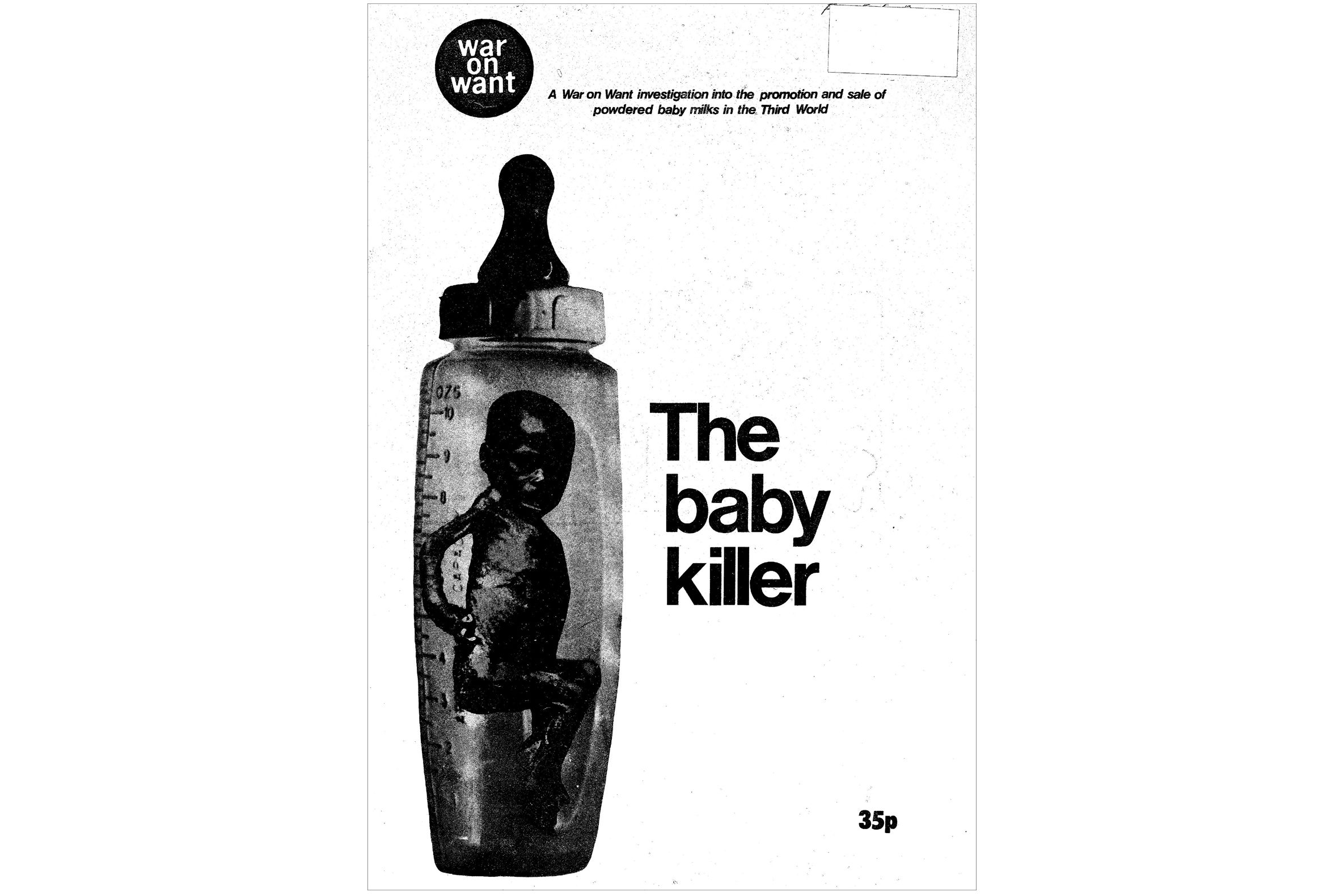

Fifty years after the “baby killers” infant formula scandal, Nestlé claims to have learned from the past and proclaims its “unwavering commitment” to the “responsible marketing” of breast-milk substitutes.

Cover of the “The baby killer” brochure © War on Want / Mike Muller

Cover of the “The baby killer” brochure © War on Want / Mike Muller

The food giant is doing everything it can to present itself as the world leader in infant nutrition, meticulously targeting each stage in a child’s first years of life. It currently controls 20 percent of the baby-food market, valued at nearly $70 billion.

Cerelac and Nido are some of Nestlé’s best-selling baby-food brands in low- and middle-income countries. According to exclusive data obtained from Euromonitor, a market analysis firm specializing in the food industry, their sales value in this category was greater than $2.5 billion in 2022.

In its own communications or via third parties, Nestlé promotes Cerelac and Nido as brands whose aim is to help children “live healthier lives”. Fortified with vitamins, minerals and other micronutrients, these products are, according to the multinational, tailored to the needs of babies and young children and help to strengthen their growth, immune system and cognitive development.

But do these infant cereals and powdered milks really offer “the best nutrition,” as Nestlé claims? That’s what Public Eye and the International Baby Food Action Network (IBFAN) wanted to find out, by focusing on one of the key public enemies when it comes to nutrition: sugar.

An unjustifiable double standard

Spoiler alert: Our investigation shows that, for Nestlé, not all babies are equal when it comes to added sugar. While in Switzerland, where the company is headquartered, the main infant cereals and formula brands sold by the multinational come without added sugar, most Cerelac and Nido products marketed in lower-income countries do contain added sugar, often at high levels.

For example, in Switzerland, Nestlé promotes its biscuit-flavoured cereals for babies aged from six months with the claim “no added sugar”, while in Senegal and South Africa, Cerelac cereals with the same flavour contain 6 grams of added sugar per serving.

In Switzerland, Nestlé’s biscuit-flavoured baby cereal contains no added sugar. In South Africa and Senegal, Cerelac products of the same flavour contain more than one cube of sugar per serving. © Anne-Laure Lechat

In Switzerland, Nestlé’s biscuit-flavoured baby cereal contains no added sugar. In South Africa and Senegal, Cerelac products of the same flavour contain more than one cube of sugar per serving. © Anne-Laure Lechat

Similarly, in Germany, France and the UK – Nestlé’s main European markets – all formulas for young children aged 12-36 months sold by the company contain no added sugar. And while some infant cereals for young children over one year old contain added sugar, cereals for babies aged six months do not.

Cerelac wheat-based cereals for six-month-old babies sold by Nestlé in Germany and the UK has no added sugar, while the same product contains over 5 grams per serving in Ethiopia and 6 grams in Thailand.

“There is a double standard here that can’t be justified,” said Nigel Rollins, scientist at the World Health Organization (WHO), when presented with our findings. For Rollins, the fact that Nestlé does not add sugar to these products in Switzerland but is quite happy to do it in lower resources settings “is problematic both from a public health and ethical perspective.” Rollins says that manufacturers may try to get children accustomed to a certain level of sugar at a very early age, so that they prefer products high in sugar. “This is totally inappropriate,” he believes.

Cerelac baby cereals wheat are sold with no added sugar in Germany and the UK. In lower income countries, but the same product comes with high levels of added sugar. © Anne-Laure Lechat

Cerelac baby cereals wheat are sold with no added sugar in Germany and the UK. In lower income countries, but the same product comes with high levels of added sugar. © Anne-Laure Lechat

On the trail of hidden sugar

The amount of added sugar is often not even disclosed in the nutritional information available on the packaging of these kinds of products. In most countries, including Switzerland and across Europe, companies are only required to indicate the amount of total sugars, which also includes those naturally present in milk or whole fruit, and are not considered harmful to health.

While Nestlé prominently highlights the vitamins, minerals and other nutrients contained in its products using idealizing imagery, it’s not transparent when it comes to added sugar. To uncover these “hidden sugars,” we obtained Cerelac and Nido products from a number of countries to examine their labels and, in some cases, have them analyzed by a specialized laboratory.

In Brazil, one of the main markets, Cerelac baby cereals are sold under the brand name “Mucilon”. The added sugar content is not declared. © Anne-Laure Lechat

In Brazil, one of the main markets, Cerelac baby cereals are sold under the brand name “Mucilon”. The added sugar content is not declared. © Anne-Laure Lechat

This turned out to be more complicated than expected. Several laboratories approached in Switzerland refused to conduct the sugar analysis of Nestlé products. One lab even wrote that it could not take part in the project because the results “could potentially have a negative impact” on its existing customers. Stonewalled, we decided to approach a lab based in Belgium. The results are edifying.

One sugar cube per portion

Cerelac is the world’s number one baby cereal brand, with sales exceeding $1 billion in 2022, according to Euromonitor. We examined 114 products sold in Nestlé’s main markets in Africa, Asia and Latin America. No less than 106 of them (93 percent) contained added sugar.

For 66 of these products, we were able to determine the amount of added sugar. On average, our analysis found almost 4 grams per serving, or about one sugar cube. The highest amount – 7.3 grams per serving – was detected in a product sold in the Philippines and targeted at six-month-old babies.

In India, where sales surpassed $250 million in 2022, all Cerelac baby cereals contain added sugar, on average nearly 3 grams per serving. The same situation prevails in South Africa, the main market on the African continent, where all Cerelac baby cereals contain four grams or more of added sugar per serving. In Brazil, the world’s second-largest market, with sales of around $150 million in 2022, three-quarters of Cerelac baby cereals (known as Mucilon in the country) contain added sugar, on average 3 grams per serving.

This product, sold in the Philippines and intended for six-month-old babies, contains almost two cubes of sugar per serving. © Anne-Laure Lechat

This product, sold in the Philippines and intended for six-month-old babies, contains almost two cubes of sugar per serving. © Anne-Laure Lechat

“This is a big concern,” comments Rodrigo Vianna, epidemiologist and Professor at the Department of Nutrition of the Federal University of Paraíba in Brazil. “Sugar should not be added to foods offered to babies and young children because it is unnecessary and highly addictive. Children get used to the sweet taste and start looking for more sugary foods, starting a negative cycle that increases the risk of nutrition-based disorders in adult life. These include obesity and other chronic non-communicable diseases, such as diabetes or high blood-pressure,” laments the expert.

“A form of colonization”

Although less pronounced, this trend is confirmed with the Nido brand, the most popular on the growing-up milks market. In 2022, global sales of Nido products for young children aged one to three had exceeded $1 billion according to Euromonitor. We examined 29 of these products sold by Nestlé in some of the main markets in low- and middle-income countries. The result: 21 of them (72 percent) contain added sugar.

For nine of these products, we were able to determine the amount of added sugar. On average, our analysis found almost two grams per serving. The maximum value – 5.3 grams per serving – was detected in a product sold in Panama.

Here are some of the Nido products examined in this investigation. On average, they contain almost 2 grams of added sugar per serving. © Anne-Laure Lechat

Here are some of the Nido products examined in this investigation. On average, they contain almost 2 grams of added sugar per serving. © Anne-Laure Lechat

With sales at around $400 million in 2022, Indonesia is the world’s leading market for Nido, known locally as Dancow. The two products for children aged one and over sold in the country contain added sugar – more than 0.7 grams per serving.

While the multinational is quick to highlight that these products are “without added sucrose,” they do contain added sugar in the form of honey. However, honey and sucrose are both considered by the WHO as sugars that should not be added to baby food. Indeed, Nestlé itself explains it very well in an educational quiz on Nido’s website in South-Africa: replacing sucrose with honey has “no scientific health benefit”, as both can contribute “to weight gain and possibly obesity”.

In Brazil, the world’s second-largest market for Nido, Nestlé claims not to add sugar to its products out of concern for children’s health and diet: “It’s ideal to avoid consuming these ingredients in childhood, as the sweet flavour can influence a child’s preference for this type of food in the future,” warns the food giant on the brand’s website in Brazil.

A shop covered with Nido products in Managua (Nicaragua). © Laurent Gaberell

A shop covered with Nido products in Managua (Nicaragua). © Laurent Gaberell

However, in most Central American countries, where Nestlé aggressively promotes Nido using influencers, the formulas for children aged one year and above contain over a sugar cube per serving. In Nigeria, Senegal, Bangladesh and South Africa – where Nido is very popular – all products for young children aged one to three contain added sugar.

“I do not understand why products for sale in South Africa should be different from those that are sold in high-income settings,” states Karen Hofman, Professor of Public Health at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg and a qualified paediatrician. “It is a form of colonization and should not be tolerated,” she adds. “There is no valid reason to add sugar to baby food anywhere,” Hofman insists.

The first two years of life

This view is shared by the WHO, which has warned for several years now about the high added-sugar content in baby-food products. “This study stresses the need for urgent action to reshape the food environment for children,” Dr Francesco Branca, Director of the WHO Department of Nutrition and Food Safety, told Public Eye and IBFAN. “Eliminating added sugars from food products for young children would be an important way to implement early prevention of obesity.”

The WHO is alarmed that obesity is dramatically on the rise, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, where it has now reached “epidemic proportions” and is fuelling an increase of non-communicable diseases such as cardiovascular disease, cancer and diabetes. Increased consumption of ultra-processed foods, often high in sugar, is singled out as one of the main causes of this epidemic.

Youngest children are not immune to this scourge: childhood obesity has increased tenfold over the past four decades, according to the UN agency. It’s estimated that 39 million children under the age of 5 are overweight or obese, the vast majority of which live in low- and middle-income countries.

“The first two years of a child’s life are particularly important, as optimal nutrition during this period lowers morbidity and mortality, reduces the risk of chronic disease, and fosters better development overall,” explains the WHO. In 2022, the UN agency called for a ban on added sugars and sweeteners in food products for babies and children under the age of three, and urged industry to “be proactive” and “support public health goals” by reformulating its baby food products.

But Nestlé seems to be turning a deaf ear to these appeals. While the multinational publicly recommends avoiding baby foods containing added sugar, these wise words don’t seem to apply to low- and middle-income countries, where Nestlé continues to add high levels of sugar to some of its most popular products.

Nestlé did not respond to specific questions about this double standard. But the company told Public Eye and IBFAN that it “has reduced by 11% the total amount of added sugars in [its] infant cereal portfolio worldwide” over the past decade and that it will “further reduce the level of added sugars without compromising on quality, safety and taste”. Nestlé also indicated that it is phasing out sucrose and glucose syrup of its Nido “growing up milks” globally. The company added that its products “fully comply” with the Codex Alimentarius and local laws.

Weak regulation

These baby-food products with added sugar are permitted under national legislation despite the fact that they go against WHO guidelines. National legislation is often based on the Codex Alimentarius, a collection of international standards developed by an intergovernmental commission based in Rome. The stated aim is to protect consumers’ health and ensure fair practices in the food trade. These standards, which gained importance as reference points for trade disputes following the establishment of the World Trade Organisation in 1995, tolerate added sugar in baby foods up to certain limits specific for each type of product – up to 20 percent in infant cereals.

Codex Alimentarius Commission meeting in Rome. © FAO / Alessandra Benedetti

Codex Alimentarius Commission meeting in Rome. © FAO / Alessandra Benedetti

Codex standards for baby foods have been strongly criticized by the WHO, which deems them “inadequate”, particularly concerning sugar, as children establish their food preferences early in life. The agency has called for the standards to be updated and brought into line with WHO guidelines, with a particular focus on banning the addition of sugars. Current Codex standards are insufficient to determine whether a food is appropriate for promotion for infants and young children, according to the UN agency.

“WHO recommendations are independent of all industry influence,” Nigel Rollins told Public Eye and IBFAN. “At Codex, you have substantive lobbying: the sugar industry, the baby-food industry, and others are all present in the rooms where the decisions are taken.” Although the Codex Commission is an intergovernmental body, industry representatives may participate as observers, or even as members of national delegations. At a recent review of the standard for follow-up formula, industry lobbyists accounted for over 40 percent of participants. For Rollins, this is the main reason why Codex standards – and by extension national laws – are less protective than WHO guidelines.

Controversial marketing practices

Our investigation shows that Nestlé uses aggressive marketing methods to promote Nido and Cerelac in low- and middle-income countries, despite the WHO’s International Code which prohibits the commercial promotion of such products. The Code, originally adopted in 1981 in the wake of the “baby killers” scandal, and clarified and strengthened by later Resolutions, bans all promotion of infant formula in order to protect breastfeeding. The ban also applies to formulas for young children and baby foods that, like Cerelac, do not meet nutrition guidelines and contain “high levels of sugar”.

Nestlé responds that it “complies with the WHO Code and subsequent WHA resolutions as implemented by national governments everywhere in the world.” “Where local law is less stringent than our Policy for implementing the Code, we adhere to our strict Policy,” Nestlé adds.

In practice, while 70% of countries have adopted laws based on the Code, many contain loopholes and implementation is generally weak in low- and middle-income countries, often as a result of pressures from the baby-food industry and exporting countries. Furthermore, the Nestlé policy neither applies to formulas for children aged one year or more, nor to other baby foods, although these are all covered by the Code.

What’s more, Nestlé promotes its Nido and Cerelac products as healthy and essential for children’s development, although they contain added sugar and carry many risks for children’s health and development. “Often manufacturers’ health claims are not supported by the science,” says Rollins, in response to reading our report. “If you have a pharmaceutical product for which you want to claim that it improves brain development in babies, or improve growth in babies, you would have to pass very high standards of evidence,” he explains. “But because it’s a food, you don’t have to pass those standards.”

In Central and West Africa, Nestlé is active on Facebook with a page called “Nido Mums”.

In Central and West Africa, Nestlé is active on Facebook with a page called “Nido Mums”.

Nutrition and health claims “idealize the product, imply that it is better than family foods, and mask the risks,” the WHO explained in a recent report that warns of baby-food marketing practices that compromise the progress made in infant and young-child nutrition. They mislead consumers as to the real content of these foods and should not be made, according to the UN agency. Yet Nestlé has made them a core pillar of its marketing strategy.

“Grow smart”

“Grow smart”. Huge billboards in the centre of Jakarta and other main Indonesian cities display the slogan. It’s at the heart of Nestlé’s campaign to promote its Nido brand, known in the country as Dancow, as the “parents’ partner for children’s growth and development”. “Inspired by mum’s love for baby nutrition, Dancow is the healthiest choice”, claims Nestlé, while failing to disclose that its product contains added sugar.

“Grow smart”. Advertising for Nido (Dancow) products in central Jakarta. Both products targeted at young children from one year contain added sugar © Ibfan

“Grow smart”. Advertising for Nido (Dancow) products in central Jakarta. Both products targeted at young children from one year contain added sugar © Ibfan

Last year, Nestlé launched a campaign aimed at “supporting the potential of children of 1 year and above in Indonesia”. The campaign managed to engage 2 million mothers in sharing “exciting moments” with their children on social media, effectively turning them into unpaid advertisers and brand ambassadors. “Thank you @dancow for accompanying my child’s growth and development,” writes one of the mothers.

Nestlé deploys the same, finely honed strategy in Brazil to promote its Cerelac (Mucilon) infant cereal brand. Its campaign is based on the concept of “nutrition enriched by Mucilon and chosen by mothers,” muses Dani Ribeiro, director of the advertising agency in charge. It plays on parents’ love for their babies, and highlights “the benefits of nutrients that contribute to babies’ immunity and brain development,” she explains. “Parents are nourished by the fact that they are making the right choice for their children,” Ribeiro adds.

In Brazil, Nestlé promotes Cerelac (Mucilon) baby cereals as being rich in nutrients which contribute to children's immunity and cerebral development.

In South Africa, Nestlé promotes Cerelac as a source of 12 essential vitamins and minerals under the theme “little bodies need big support”. “For over 150 years, generations of parents have trusted Nestlé Cerelac to provide just what their baby needs,” trumpets the multinational. Yet all Cerelac products sold in this country, which is facing a veritable obesity epidemic, contain high levels of added sugar.

In South Africa, Nestlé is promoting Cerelac baby cereals under the theme "little bodies need big support". All products contain a minimum of one cube of added sugar per serving.

Chris Van Tulleken, Professor at the University of London and author of the best-selling book Ultra-Processed People, which explores the pervasiveness and impact of ultra-processed food, is extremely concerned about the marketing strategy used by Nestlé. “These are not healthy products. They are not necessary. They are inferior to real food,” he stated. “These types of products are part of a global nutrition transition to an ultra-processed diet which is associated with weight gain and obesity, but also many other adverse health outcomes."

An “educational” platform

Nestlé pioneered “medical marketing,” involving a set of techniques that have become standard practice in the industry today, says Phillip Baker, a senior research fellow at the University of Sydney in Australia and author of numerous studies on the subject. The strategy is based on strengthening links with health professionals and obtaining the endorsement of leading scientific authorities, while positioning the company as a partner for parents in the nutrition and development of their children.

While the main goal is to increase sales on the baby-food market itself, it plays another key role for Nestlé: developing loyal consumers for life. Baker describes it as a “cradle-to-grave marketing strategy.” “The idea being to get consumers from a very young age, develop that brand loyalty, develop those taste preferences for their products”, he explains.

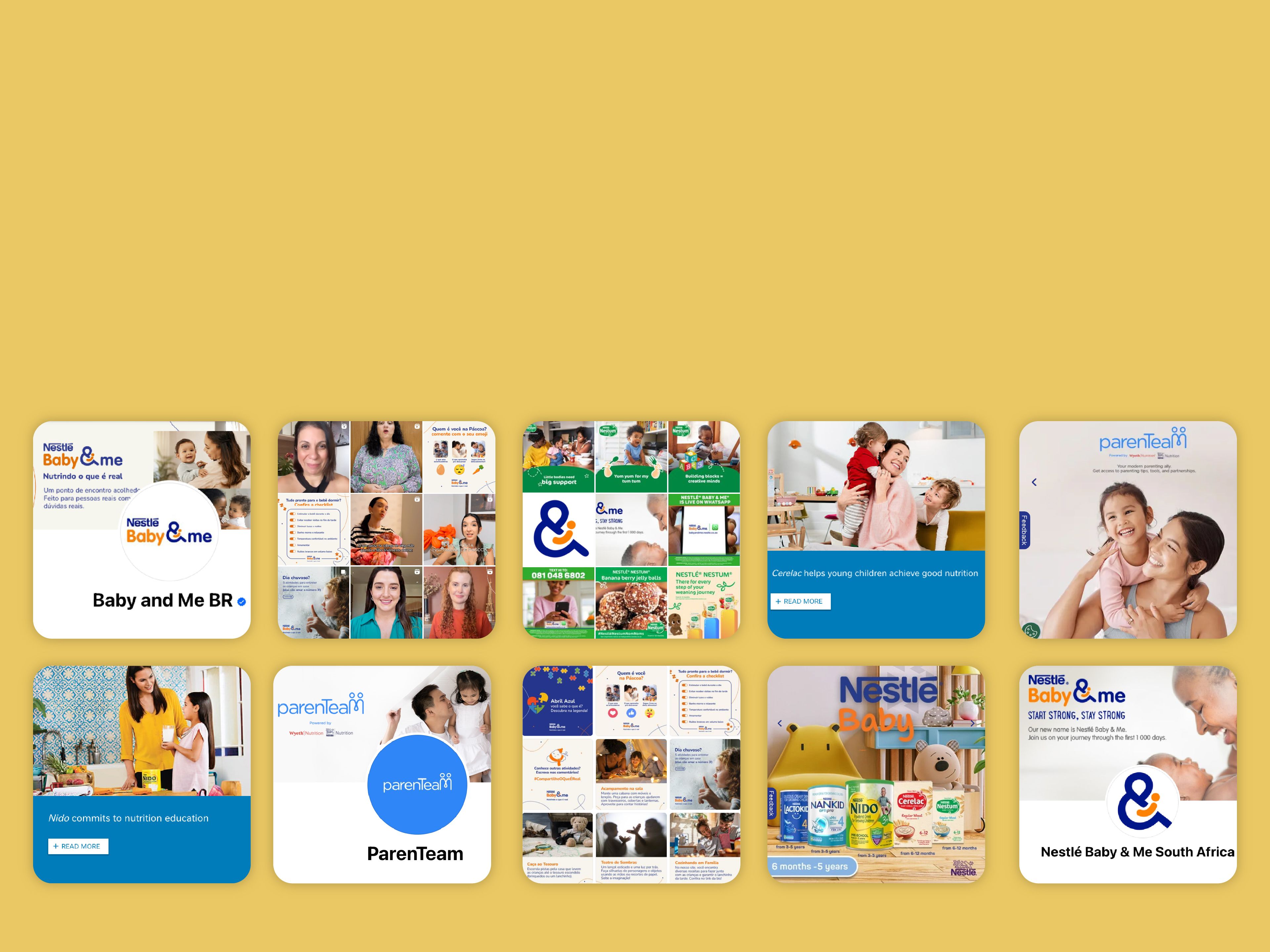

Nestlé has created Baby and Me, an “educational platform” available in over 60 countries, with the stated aim of promoting healthy eating for babies and offering “expert-backed” information. Parents looking for information on infant nutrition may be directed to this platform and be exposed to content that steers them towards Nestlé products.

Nestlé has created the “Baby and Me” educational platform, whose stated aim is to promote healthy eating for babies and provide information that is “expert-backed”. But the advertising is never far away.

Nestlé has created the “Baby and Me” educational platform, whose stated aim is to promote healthy eating for babies and provide information that is “expert-backed”. But the advertising is never far away.

“Parenteam,” the Filipino version of the scheme, offers ovulation and pregnancy calendars as well as a due-date calculator. In South Africa, parents can access a “major moment checklist” to help them “win in every aspect of modern parenting”. Mexico has an allergy calculator and Brazil a guide to finding the perfect name. These websites are packed with advice, tools and recipes designed to attract parents. But ads for Nestlé products and “buy now” buttons are never far away.

Experts in white coats

Nestlé regularly organizes events on the Nido and Cerelac online channels with health professionals. Although most of the time the experts speak about child-nutrition related issues and do not directly promote the products, the Nido and Cerelac brands feature prominently, leading parents to believe that these products are endorsed by eminent scientific authorities and that Nestlé’s health and nutrition claims have scientific support.

Our investigation also uncovered cases of experts in white coats directly promoting Nestlé products. “Nido’s specialized nutrition system is designed to protect every stage of your child’s development,” explains nutritionist Kenia Lawrence in a video posted on Instagram in Panama. “Nido1+ helps protect and strengthen the immune system, thanks to probiotics and prebiotics, and contains key nutrients for child development.” Not a word on the one and a half sugar cubes added to each portion of the product in question.

For Baker, it is evident that “by using health professionals, the companies powerfully shape parents’ decision making”. An influence that “can very often be harmful,” he believes. This practice also goes against WHO guidelines, which state that manufacturers must not encourage healthcare professionals to support and recommend their brands and products.

In a recent report, the UN agency severely criticized the marketing practices used by the baby-food industry to promote its products online, pointing the finger at the use of various strategies that are often not identifiable as advertising. These include the use of baby-clubs, as well as the use of health professionals and influencers such as Meagan Adonis and Billy Saavedra. The UN agency called on manufacturers to put an end to their “exploitative marketing practices”.

Nothing can justify the double standards highlighted by the Public Eye and IBFAN investigation. If Nestlé truly intends to act responsibly, it must follow the recommendations and guidelines of the WHO and stop getting babies and young children hooked on sugar, regardless of the country in which they were born.

This article was amended on 6 June 2024 to slightly correct some figures related to the number of Cerelac and Nido products examined by Public Eye and IBFAN.

Swiss NGO Public Eye offers a critical analysis of the impact that Switzerland, and its companies, has on economically disadvantaged countries. Through research, advocacy and campaigning, Public Eye also demands the respect of human rights and of the environment throughout the world. With a strong support of some 28,000 members, Public Eye focuses on global justice. Reports like this one are only possible thanks to the people who support us: with a donation, you help us remain entirely independent.

Imprint

Text: Laurent Gaberell, Manuel Abebe, Patti Rundall

English translation: Manuel Abebe

Editing: alphadoc

Web implementation: Fabian Lang, Rebekka Köppel